MILL HOUSE, MILLERS & THE WINDMILL IN THE 19th CENTURY

Although this is very well documented period in Bridgham’s history the occupation of Mill House is a confusing one. This is due in part to the fact that for the first 75 years of the century, there was a working mill with named millers. However, the millers did not always live in Mill House. It becomes more confusing as the owners of Mill House were not always millers and they may or may not have lived there either. Finally, the occupiers are the most difficult group to discern as most of the censuses from 1841 to 1901 fail to list the name of the house. It is not safe to assume that because a man is listed as a miller in the census, that he is living in Mill House. On some occasions the occupier is neither the owner nor the miller. If one consults the trade directories of the time, the name of the miller can be a big surprise as there is no evidence of the person living anywhere in Bridgham. But as censuses are only every decade, we can’t be sure whether they commuted to work in Bridgham or lived here.

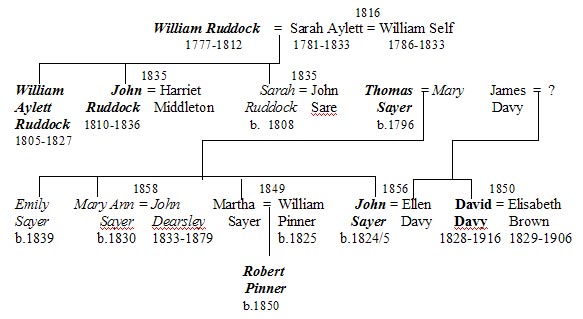

One branch of the Ruddock family first appears in the Bridgham parish registers in the 1780s. William Ruddock is the first named owner in 1805. He was married to Sarah Aylett and had at least five children: Elizabeth (born 1803), William Aylett (1806), Sarah (1808), John (1810), Robert Henry (1811). The John and Mary Ruddock who appear in 1780 are probably his parents as they are living in Mill House prior to enclosure. (So the house was built some years before the mill was new built c.1808 - which may hint at a rebuild)

1804 saw the passing of the Enclosure Act for Bridgham. Enclosure was the fencing off and redistribution of land. It took a few years to sort out all the implications of the Act, the Award being produced in 1806. William Ruddock, carpenter, already held (other) land in Bridgham as the Manorial Court Book record for 13 th February 1807 makes it clear that he is receiving Mill House and Mill Field as a copyhold tenant for ever ‘in lieu of his former lands and tenements holden of this manor’ for a quit rent of 2d annually. The copyhold fee is a guinea. Clearly he had lost some land and property as a result of enclosure and Mill House and Mill Field were his compensation. He also had to pay a proportion of the fee for enclosing the lands of Bridgham. His contribution was £4/5/-. To get this in perspective, the total was £1,494 17s 6d with the two main landowners paying over £1,400 between them and the remaining ten men all paid less than £20.

The Enclosure Award of land contains the first written description of Mill House and moves on to Mill Field:

William Ruddock, carpenter - a copyhold tenant .

"First, one piece containing 23 perches bounded

by the Town Street Road towards the North,

by land allotted to Robert Algar the elder towards the East,

and land thereby allotted to John Pilgrim towards the South and West.

Second, one other piece containing 3 acres and 16 perches bounded

by the Larling Road towards the North,

by land allotted to John Brame in part towards the East,

by the aforesaid Town Street Road in part towards the South,

by lands allotted to John Sterry in part towards the West and another part of the South, by land allotted to Robert Algar the elder on other parts of the South and East,

by land allotted to John Sare on other part of the south and on the remaining part of the East (should this be west?)

by the aforesaid Town Street Road on the remaining part of the South, and

by the Roudham Road on the remaining part of the West."

Thirty years later William’s daughter, Sarah, married a John Seare – perhaps his neighbour’s son. A messuage is property law term for a dwelling-house together with its outbuildings and surrounding land. Copyhold is where the evidence of tenure of house/land is recorded in a court roll. The ‘tenant’ is able to buy and sell but only by coming before the court and paying a fee. The Court Book states that:

In this court William Ruddock did by the rod surrender out of his hands of the Lord of the manor all and singular his messuage lands, tenements and herediaments whatsoever holden of this manor by copy of court roll.

At the same court sitting, he obtains a mortgage on Mill House for £150 from John Smith - nearly double its value of a century later! The court book makes no mention of who the miller is.

William Ruddock died on 12 January 1812. He was 35 with five children under 10 years of age. His widow, Sarah was clearly grief-stricken. His gravestone in Bridgham churchyard is one of the oldest that can still be read:

Time swept by his o’erwhelming tide,

My faithful partner from my side

And you of yours depriv’d maybe

As unexpectedly as me.

Set then your heart on things above,

Death soon will end all mortal love.

The manorial court did not meet regularly, so it is over two years before it addresses the inheritance of Mill House. On 10 August 1815, the court accepts that William’s eldest son, William Aylett Ruddock, inherits the property, but as he is only nine his mother is given wardship of both him and Mill House until he is 21, in 1826.

Life expectancy at the time was not high, but the Ruddocks seem particularly unfortunate. Sarah remarried on 1 st August 1816. Her new husband William Self was five years younger than her. Two years later, Thomas, probably their first child, died aged 8 months. William Ruddock the elder’s likely parents, John and Mary reached their allotted span of three score years and ten, dying in 1821 at 70 and 1825 at 74 respectively. But a year after reaching his majority, William Aylett Ruddock dies at 22 in 1827. His epitaph is also intact:

Physicians came in vain.

Death did ease and God did please

To rid me of my pain.

The next eldest brother, John, should now inherit but he is only 17. He fails to attend the first court meeting and so the decision is held over until 25 June 1828. He has to pay an inheritance fee and a fine for his previous non-appearance totalling £23. This seems a hefty amount considering most of the village were considered poor enough to be eligible for charitable status. For this they had to earn under £21 a year! John was unable to pay the £23, so it was loaned him by his step-father William Self with John promising to pay him back before his 21 st birthday. Further sorrows are in store, for both John’s mother, Sarah, dies in August 1833 at 52 and her second husband, William, follows her that November at 47. The rector of Bridgham throughout this woeful period for the Ruddocks was the Revd. Stephen George Comyn, whose main claim to fame was as chaplain to Nelson on three different ships. He was with Nelson at the Battle of the Nile before settling in Bridgham in 1802. He buried all these Ruddocks, and sadly, officiated at more Ruddock funerals than marriages.

In 1835, John Ruddock is the first member of the family to be described as Corn Miller (in White’s Directory). This is a good year for John, as he marries Harriet Middleton on 17 th October. But tragedy is never far away, for John dies the following year on 27 th May. The court records are rather confusing at this point. Firstly, the court confirms that there are no outstanding mortgages or loans on Mill House (going back to John Smith’s of 1807 and William Self’s twenty years later). Curiously, John Ruddock was said to be living at Gasthorpe from as early as 1832. Was he commuting to work at Bridgham? Even more surprising is that when his widow, Harriet, attends the court she has to travel from her new home in Dereham. John Ruddock, following his father’s and elder brother’s example, had mortgaged Mill House to Rebecca Hastead for £160 and also secured a loan from Robert Everett of £10. All the debts were paid off before his death. Ruddock remembers his half-brother and half-sisters, Robert, Mary and Emma Self, in his will, which was written 13 days before he died.. He leaves them £10 each for when they come of age at 21, but only if his wife can afford it. No sooner does Harriet inherit Mill House, but at the same court sitting she sells it to Robert Everett, who buys it for his wife, Sarah, for £250.

Inheriting Mill House seems to be the kiss of death at this time. The property had five owners in a twenty-two year period. Robert Everett fares little better, for nine years later it is transferred to his widow, Sarah. He leaves her in his will:

"...my windmill, with all the machines, going gears and appurtenances, and the piece of land on which my mill stands …"

Just over a decade later, her grandson, Edwin Thomas Everett, inherits Mill House on 16 October 1856. The description of the property has a better description of the house in her will and it takes into account the presence of the windmill:

"…all that my cottage or tenement with the barn stable and appurtenances thereto belonging and also my windmill and the going gears…"

Although a grandson, and therefore considerably younger than his grandmother Sarah, Edwin dies just ten years later. Edwin is described as a gentleman of the city of Norwich, so clearly was neither a miller nor an occupier. Perhaps local families had enough of the ‘curse’ of inheriting of Mill House, for this time it is not bequeathed but sold by auction. The successful bidder on 1 st April 1865 is William Duncan of 48, Oxford Terrace, Hyde Park, Middlesex! He paid £280 and the land tax was 12s with an annual quit rent of 10s. I have no idea what he would want with it. Local knowledge states that the windmill was a post mill. The court book for this change of copyhold confirms this. Included in the sale are:

"…the post mill and tackle and going gears, utensils and implements, machinery and apparatus…"

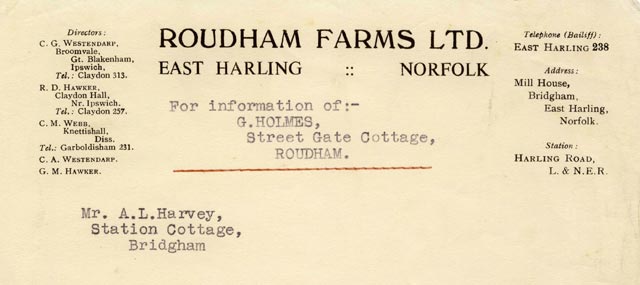

It also confirms that the house is in the occupation of Thomas Sayer. William Duncan is a widower who by 1875 has moved, but only round the corner to 83, Gloucester Terrace in Hyde Park. He appears in the list of electors, which means he had bought the freehold in the interim and was no longer a copyhold tenant. Thus, there are no more transactions in the Court Books concerning the property. His last mention is as a registered elector in 1890, so presumably died a short while after. He held Mill House for 25 years, far longer than anyone else in the 19 th century.

I cannot locate to whom he left Mill House without looking up his will in London. Then, in 1905, it is sold by Charles Arthur Duncan (clearly a relative) of 5 Windsor Mansions, Northumberland Street, Baker Street, London for just £80 to Thomas Wincup Newson. So in the hundred years since being awarded to William Ruddock, Mill House has been inherited six times but only sold thrice. The original mortgage of £150 doesn’t necessarily reflect the full value. The purchase prices of £250 and £280 in 1836 and 1865 must allow for a working windmill. By 1905, this is no longer the case, hence the knock down price of £80.

Schoolboys of a century ago, such as Roper Reeve, Alf Meek and Reggie Cole recalled playing around the base of the old mill. Roper Reeve recorded the following in his memoirs:

“There was a windmill in Bridgham years ago, standing and working on the field at the back of the old Wesleyan Chapel [village hall]. The field is still known as Mill Field. During my school days there was about four feet of the brick wall circle standing and we used this for running round and play pens. The entrance was from a gate in Green Lane.”

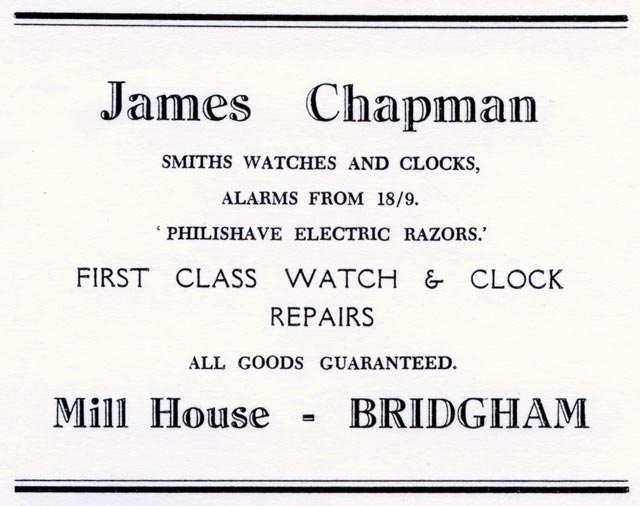

Jimmy Alderton, born 1907, was the ‘youngest’ person I have met who could recall the ruins. Sonny Chapman, 90 this year, did not come to the village until 1919 and there was no trace of the mill then. Perhaps the debris was cleared away for use in the war effort, or maybe locals used it as a handy source of material. The clearance, though, is utterly complete. In 60 years of ploughing Mill Field, the Chapmans never found a trace of the windmill apart from an area of the field which is more chalky than the rest - a mill that has gone with the wind!

It is only in this mid-century period of 40 years that I have been able to discover the names of the Bridgham millers. They change so often, that one wonders if milling was a going concern – though the Ruddock managed to pay off all their loans. (They obviously didn’t have an endowment mortgage!) Clearly, all was over by the end of the century as there is no mention of a miller at all and it was in ruins by 1900. So, there was money in milling but the condition and age of the mill at Bridgham may have prevented the miller doing a good job or severely reduced his profit. The names of the millers come from three main sources: trade directories such as Kelly’s, census returns and the tithe award of 1838. They are, with the years they are known to have been the miller:

- John Ruddock, 1835, mentioned above. He inherited the mill at 17 in 1827 and was only 25 when listed as the corn miller. Where he learned his trade is a mystery as his father was always described as a carpenter. However, several other known millers have also been called carpenters. Perhaps this was a dual occupation. How he managed the mill when he lived in Gasthorpe for the last few years of his short life is not known. He died the following year

- William Hart Wilton, 1841-45. Another young man. He was 25 in 1841 and living with his father and step-mother, Edmund and Sophia Wilton at Rose Cottage on census night. His father was another of the Bridgham carpenters. Later the same year, William marries Elizabeth Burston or Brewster on 24 th October. Their subsequent children are Emma (b.1843), Ellis Gapp (1845), Robert Andrew (1846/7), Lucy Hart (1848) and Charles William (1851). He is still the miller in 1845 but by the next census in 1851 he gives his occupation as journeyman carpenter. He is succeeded as miller by his younger half-brother.

- Jonathan Wilton, 1851. Jonathan was named miller in census year, yet was only 21. It is clearly a young man’s profession - before they die prematurely or move onto something else. At least, that is how it seems in the first half of the century. Their father Edmund’s first wife was Martha, and their children were Mary, Elizabeth, Elsie, Edmund, William, Charles and Bennett. Jonathan was the first child of Edmund’s second wife, Sophia and was followed by Anne, Hannah, Maria, and Ellen. Of these twelve children, Mary died aged 11, Hannah at 14 and Ellen at just a few months old. Jonathan and Hannah were baptised just after they were born in 1830 and 1833. Their parents must have forgotten this for they were done again as part of a job lot with a new sister in 1837! There is no trace of Jonathan in the village after 1851. He may have married and moved away or sought a different occupation elsewhere, like his brother William.

- Potter Batson, 1854. The only other fact known about Potter Batson’s connection with Bridgham is that he and his wife Sarah buried their daughter Charlotte Ann here in 1854. This is the same year he is listed as miller, so may have not stayed here long. The tragedy of losing their daughter may have prompted them to move on. It is such a rare name that I was surprised to find another Potter Batson, an Aylsham butcher, dying five years before. He left a curious will in which no family members are mentioned. Surely the two men are related – the combination of names is so unusual. Perhaps the butcher was the father of the miller and they weren’t on speaking terms. I sense a family drama here.

- Thomas and John Sayer or Sare, 1856. Thomas bucks the trend of young millers. He is 60 in 1856 and has had considerable milling experience, being a miller for much of his working life. Although the Sare/Sear/Sayer family had been in Bridgham for generations, he was actually born in Shropham. He is the first miller since John Ruddock that we can be sure lived in Mill House. He was also a local preacher and perhaps took services at the Wesleyan Chapel which abutted Mill Field. The chapel was erected in 1834. He lived in Mill House with his wife Mary and daughter Emily who, by the census of 1861 was 22 and a dressmaker.

There was also a servant living in the house on the 1861 census night. This was William Bowen aged 17 from Rocklands whose occupation is given as miller. He was presumably Thomas Sayer’s assistant at the mill and may have done the lion’s share of the work, perpetuating the village tradition of it being a young man’s trade.

Thomas and Mary had at least another five daughters: Sarah Ann and Elizabeth (who both married shoemakers), Betsey, Charlotte and Martha, (who married William Pinner in 1849). I have found only one son, John, who left home as well as marrying - for which his parents must have been truly grateful. He was a miller at the time of his marriage in 1856, so presumably assisted his father.

- J.Whitehead, 1864. There were Whiteheads in Bridgham from 1722, but no J. Whitehead who fits the bill unless he is over 80! Presumably a mistake for Thomas . This miller is listed in White’s directory and that is all I know of him. It is strange that Thomas Sayer has moved on after such a short time though he may have died. It is odder that he came to Bridgham in the first place, having spent so much time in Shropham. I suspect that many of the Sare/Sayers in the Bridgham were his relatives and that is what drew him here; that and perhaps the Wesleyan Chapel.

- David Davy, 1868/9 The Davy family lived diagonally opposite Mill House in the White Lion when it was a beer house. The Davys were also carpenters and David himself described himself as one when he signed his daughter’s marriage certificate. As far as I have been able to discover he and his wife Elsabeth had just three girls (a small family for the times and one of these died in infancy. One of the Davys, and I am fairly sure it was David, was a skilful sign writer whose work was seen on many tradesmen’s carts in the area. Roper Reeve recalls running errands for him as a young boy in the early years of the 20 th century. He sent boys to buy his tobacco for smoking or chewing. He bought it ½ oz. each time price 1½d and the brand was Dog & Monkey.

- Robert Pinner, 1871. Like Thomas Sayer, he also lived in Mill House and was born is Shropham, but like many of the other millers was young, just 21, and unmarried. He is actually listed as a master miller and is the grandson of Thomas Sayer.

- George Pitcher, 1872. He seems to be the man who never was. His name appears for one year only and there is no trace of him or his family in the census or parish records. He obviously arrived soon after the 1871 census and went before the next one.

- George Tuck, 1874. At his marriage in 1874, at the age of 22, his occupation is given as miller, but it is not known if this is in Bridgham. By the time his children are getting married he has changed trade to that of keeper. The mill was no longer in use by then. He turned to gamekeeping.

- David Davy, 1875. For a couple of years in the early 1870s David Davy appears to have relinquished the mill to others. Perhaps he wanted to pursue his other occupations; by 1883 he is described as carpenter and shopkeeper. He died in 1916 aged 88.

- George Tuck, 1877. This time, George is named as the miller of Bridgham in the trade directory. He seems to be the last miller of Bridgham. The mill was still in use as a grocer’s shop in 1882, and George Tuck was the village grocer by 1883. It is not certain that he lived in Mill House, but his daughter, Frances, married Herbert Stammers in 1899, and they moved into Mill House around 1913. A year later, George remarried at the age of 62, his trade then being market gardener.

The 1881 census and the succeeding trade directories all fail to list a miller. So this was the end of one of Bridgham’s principal trades and buildings after many hundreds of years.

FAMILY CONNECTIONS

The main names that recur as either owners, millers, residents or with business connections are Ruddock, Sayer, Davy, Dearsley and Pinner. Bridgham is a small village and there was considerable intermarrying between the various families. The connections between the above families though, is more than coincidence as it help explain where the next owner, tenant of miller came from. The White Lion and its occupants have a link with Mill House as well. here are a few of the connections:

in bold = miller in italics = known to have lived in Mill House

- 1806, William Ruddock’s Mill field abuts on to the land of John Sare

- 1813 or before, Rebecca Hastead provides a mortgage on Mill House

- 1834, John Ruddock sells the White Lion to James Davy (father of David) which is in the occupation of John Dearsley senior

- 1835, Sarah Ruddock, (John’s sister), marries John Sayer/Sare (any relation?)

- 1841, William Cutter lodges at Mill House, his mother: mortgagee Rebecca Hastead

- 1856, a different John Sayer (son of Thomas Sayer) marries Ellen Davy (daughter of James & brother of David)

- 1858, John Dearsley junior marries Mary Ann Sayer (daughter of Thomas Sayer)

- 1871, Robert Pinner, miller, is grandson of Thomas Sayer and nephew of John Dearsley and Ellen Davy, and possibly great-nephew of Sarah Ruddock, thereby linking four or five of the principal names.

As mentioned earlier, this is the least clear cut of the three groups to determine. I assume that the Ruddock family were living in Mill House before and after the enclosure award of 1806. This family group comprised William and Sarah, their five children and most likely William’s parents, John and Mary, as well. When Sarah married William Self following William Ruddock’s death, it is likely that he moved in with her as he loaned the money to his stepson, John, so that he could inherit Mill House as copyhold tenant.

For the next 20 years, Mill House was owned by members of the Everett family. They were based in East Harling, were not millers and there is no evidence they ever lived in the house. However, 1838 saw the execution of the Tithe Award. The map and accompanying text reveal that although Robert Everett owned Mill House and Mill Field, the house was occupied by two families, that of James Ludkin and William Cutter. They were still there three years later on the 1841 census night.

James Ludkin was a shoemaker. He married Elizabeth Brown in 1834. By the time of the census they had produced five children: David Cornelius (born out of wedlock in 1833), Mary Ann (1834), Elizabeth (1837), James (1835) and Robert (1841). Ludkin’s wife died the following year. She was 36. There is no record of the Ludkins in the village after this time.

William Cutter was a member of a well-known Bridgham family. Like several of his descendants he was a blacksmith. His mother was Rebecca nee Hastead, to whom John Ruddock has mortgaged Mill House in the 1820s. William married Maria Cooper in 1837 so starting their married life in Mill House, but sharing it with another family. He was 21 and she, 20. At the time of the 1841 census they had John aged 2 and Rebecca 3 months together with the luxury of a live-in, 45-year old nurse called Jane Brindle. This gives a total of five adults and six children! (David Cornelius Ludkin is not listed – he may have died, been staying elsewhere or been brought up by grandparents, as often happened to illegitimate children). It is not like the extended Sayer family of two decades later. How did two families and a nurse all live together? The rooms are easily split downstairs, but upstairs, with six young children, must have been a nightmare! The census indicates that the building was divided into two.

By the time of the next census, the Ludkins had left Bridgham and the Cutters had increased their family with Mary Ann, 7 in 1851, William 6 and Albert Isaac 1. But they didn’t stop there! Clara Maria came along in 1855 followed by Henry Augustus two years later. There is no certainty that the Cutters were by then at Mill House. The house is not named on the census and the Cutters are listed next to the Brames who lived at the Red Lion. As the blacksmiths was near there, it’s highly likely the Cutters had moved next to William’s place of work. There is no record of any of their seven offspring dying in childhood, but their father was buried when the youngest, Henry, was nine. William Cutter was just 49. This means that, in 1851, we don’t know who was at Mill House.

In 1861 and 1871 it is the Sayer family, mentioned earlier under millers. Thomas and Mary said they were 46 and 42 twenty years before in Shropham. In 1861 they lay claim to 65 and 63! Folks seems quite slack in this regard. As well as them, Emily Sayer and William Bowen, also living at Mill House in 1861 and described as lodgers, were John and Mary Ann Dearsley/Darsley (aged 28 &27) and their two children Frederick John aged two and Susan, one. Frederick was born before she married and he bore the name Sayer rather than Dearsley until he died. One can imagine what her lay-preaching father thought about this! JohnDearsley died early, aged 46 in 1879. His parents outlived him by quite a few years.

Where all the 1861 residents slept and how they managed to live together is a mystery. The four bedrooms probably housed 1) Thomas and Mary; 2) Emily; 3) John, Mary Ann, Frederick and Susan; and 4) William. Of course, the young Dearsley family may have had one of the downstairs reception rooms instead of or as well as a bedroom. There are two doors leading off the front door – highly suitable for lodgers, even if they are family!

There is lot more room in 1871, when there are only two residents: Emily Sayer and her nephew Robert Pinner. Ten years before, Emily was a 22-year old dressmaker; now she is housekeeper to her nephew. They are only ten years apart in age. Her older sister, Martha, is Robert’s mother, having married William Pinner in 1849.

In 1881, the Mill House is not specified but Frederick Sayer was living in the village. He, like Robert Pinner, was a grandson of Thomas Sayer. He married Catherine Bassingthwaite the year before, when they were both aged 22 and his occupation is that of groom. They may be living at Mill House, we just don’t know. There are also Daselys in the village and George Tuck is living very close to the Reeves and Davys, who were known to live adjacent to and opposite Mill House. It’s anyone’s guess.

The census is no clearer in either 1891 or 1901. So there is a 35-year gap between Robert Pinner and his aunt living there in 1871 and Arthur and Grace Stammers in 1906. Each census lists a few uninhabited houses and there is always the possibility that with the mill in ruins, no one was living in Mill House. This might explain why it sold for only £80 in 1905.

David O'Neale - 20th January 2008